BrainFartLab

Passion projects and ruminations related to IT development.

Project maintained by brainfartlab Hosted on GitHub Pages — Theme by mattgraham

Related

- Cellular Automata: introduction

- Cellular Automata: simple automata

- Cellular Automata: mobile automata

Cellular Automata: mobile automata

With the simple automata wrapped up we continue with a different class of automata, called “mobile automata”, for which we refer to chapter 3 of New Kind of Science. This article will deal with the implementation insights we gathered along the way.

Compared to simple automata, the mobile class introduces the concept of “states”. States are essentially markers for those cells which we update in a given iteration. The next iteration may have different cells marked as states, determined by the rule. In comparison, with simple automata all cells are updated in each iteration. In mobile automata however, only state cells receive an update. On the one hand this reduces computational time, on the other it introduces more memory requirements, since we need to keep track of which cells are marked as states.

The implication on the implementation will mainly be centered around the following topics:

- How will we perform data modeling?

- How do we pass rule configurations between the web app and the WebAssembly component?

- How do we allow users to modify the progeny (cell outcome) and the mobility (which positions will be states in the next iteration) through UI interactivity?

In addition to these questions this project will see a rampup in unit testing strategies, both on the WebAssembly and the Elm front. With the codebase expanding and requiring frequent iterations, this will help to maintain consistency of result.

Mobile automata

As mentioned before, mobile automata are covered in chapter 3 of NKS. in NKS, we distinguish between 3 subclasses of mobile automata:

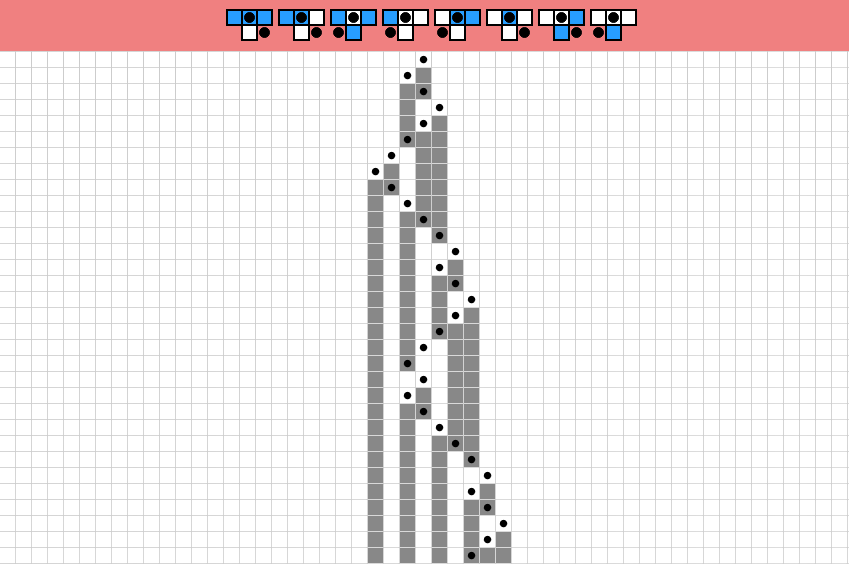

Simple

We look at the combination in the window centered at the state cell to determine its progeny and the next state cell (within the window).

Simple rule example

Simple rule example

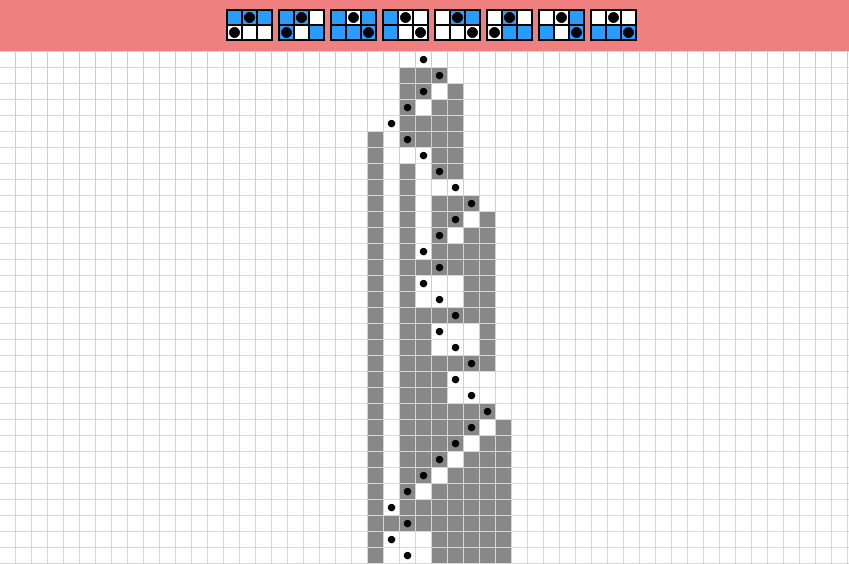

Extended

Similar to simple except the progeny is no longer limited to a single cell but all cells in the window; this implies we shouldn’t have more than one state cell to avoid overlapping windows and thus conflicts in progeny.

Extended rule example

Extended rule example

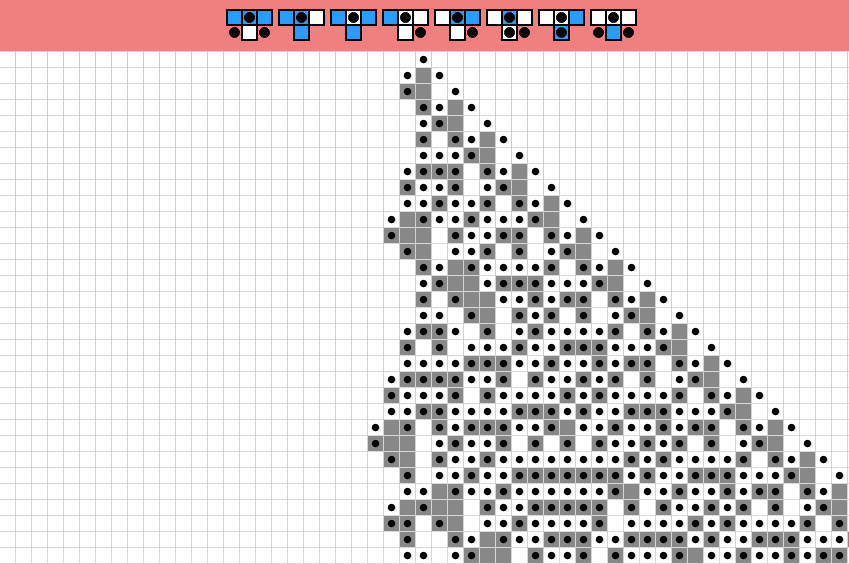

Generalized

In contrast to the extended case, a single cell is updated but it can introduce multiple new state cells within the window; the number of state cells in the universe can grow/shrink.

Generalized rule example

Generalized rule example

Rust

The Rust implementation was once again straightforward. We already had some structure in the “simple automata” case with a Statetrait. Back then this was just empty, but this time around we implement said trait to include a data structure for tracking all cells marked as states. This state object will be passed in the apply method of the structure implementing the Rule trait, where it will be read and modified:

trait State {}

#[wasm_bindgen]

pub struct MobileState {

positions: HashSet<usize>

}

#[wasm_bindgen]

impl MobileState {

pub fn new(span: usize) -> MobileState {

let positions = HashSet::with_capacity(span);

MobileState {

positions,

}

}

pub fn add_position(&mut self, position: usize) {

self.positions.insert(position);

}

pub fn contains(&self, position: usize) -> bool {

self.positions.contains(&position)

}

pub fn get_positions(&self) -> Vec<usize> {

self.positions.iter().map(|i| *i).collect()

}

fn update_positions(&mut self, positions: HashSet<usize>) {

self.positions = positions;

}

}

impl State for MobileState {}

trait Rule<T: State> {

fn apply(&self, state: &mut T, universe: &mut Universe);

}WASM unit testing

Aside from unit testing as usual of code internals, we include more tests in the WASM framework. Given the more complex the automata rules are becoming in the mobile case (progeny & mobility), we opt to cease working with a rule index and instead manipulate progeny and mobility for single combinations of cells directly through our API. This requires mappings between Javascript and Rust types. One example is the Outcome struct constructor, which serves as a representation of a combination with its progeny and mobility:

#[wasm_bindgen]

pub struct Outcome {

progeny: BitVec,

mobility: HashSet<i32>,

}

#[wasm_bindgen]

impl Outcome {

pub fn new(progeny_values: Vec<JsValue>, mobility_values: Vec<i32>) -> Outcome {

let mut progeny = BitVec::repeat(false, progeny_values.len());

progeny_values

.iter()

.map(|v| {

v.as_bool().unwrap()

})

.enumerate()

.for_each(|(i, b)| {

progeny.set(i, b);

});

let mut mobility: HashSet<i32> = HashSet::new();

mobility_values

.iter()

.for_each(|&i| {

mobility.insert(i);

});

Outcome {

progeny,

mobility,

}

}

}

#[wasm_bindgen]

pub struct MobileRule {

span: usize,

cases: Vec<Outcome>,

}For this reason we must have access to specialized test classes. The result can be seen here. Testing can then be performed with

wasm-pack test --nodeWith the API of our WebAssembly code properly testing, we can omit our Rust code from future searches of configuration errors.

Elm

Surprisingly, the Elm work took a very long time until I was satisfied with the code. I spent a great deal on the data modeling, trying to figure out what works best and it goes to show there is still a lot to learn about data modeling in a functional language, especially as you strive to make impossible states impossible.

Data modeling

Fragment module

The bulk of the data modeling was focused on the representation of combinations, progeny and mobility. These three combined make up an outcome. When we aggregate all outcomes (one for each combination) they make up a rule. To represent a window of cells (e.g. a combination, but could also be a progeny) we created an opaque Elm type called a Fragment. Internally a fragment has a middle value and two arrays of equal length (denoted as “span”; window = 2*span + 1) to make up the sides next to the middle value.

The symbols making up the cells can be any type, thanks to extensible records:

type alias Span = Int

type alias Side a = Array a

type Fragment a

= Fragment (Side a) a (Side a)Whilst one can debate the merits of this type versus a simple List or Array, it does make it slightly easier to use relative indices to access the cell status. If the index is 0, return the middle element, if it is larger than 0, use the index on the right side, if negative, take the absolute value and access the left side of the fragment. The same applies to modification as well.

One could take it a step further and use phantom types to enforce some sort of equal length condition on the sides making up a fragment:

type alias Span = Int

type alias Side span a = Array a

type Fragment span a

= Fragment (Side span a) a (Side span a)Through our module we can control how these fragments are made and return errors in case of a faulty construction. Functions are included to create all possible fragments of a certain span given a list of symbols to represent the cell values:

getFragments : Span -> List a -> List (Fragment a)

getFragments span symbols =

if span == 0 then

symbols

|> List.map (\s -> (newFragment s 0))

else

let

sides : List (Side a)

sides =

permutations span symbols

in

sides

|> List.map (\left ->

symbols

|> List.map (\middle ->

sides

|> List.map (Fragment left middle)

)

|> List.concat

)

|> List.concat

permutations : Span -> List a -> List (Side a)

permutations span symbols =

if span > 1 then

product (permutations (span - 1) symbols) symbols

else

symbols

|> List.map (Array.fromList << List.singleton)

product : List (Side a) -> List a -> List (Side a)

product sides symbols =

symbols

|> List.map (augment sides)

|> List.concat

augment : List (Side a) -> a -> List (Side a)

augment combinations symbol =

combinations

|> List.map (Array.push symbol)With these functions we created a clean interface that can deal with different spans and symbols (+ cardinality). As a sidenote, this is a clear example of some overengineering by design for the purpose of learning, since we use a span value of 0 or 1 and our symbols are either Dead or Live.

Rule module

The rule module again was a source of a lot of inner contention and although a straightforward way of incorporating all the rule types (simple, extended & generalized) might have been accomplished with a union type:

type Rule a

= SimpleRule Span (List (Case a))

| ExtendedRule Span (List (Case a))

| GeneralizedRule Span (List (Case a))We opted for a separation of the rule type into its own union type. Though we could do it without, visualization of a rule of a certain type can be made little easier with a union type and an API method to return said type for a supplied rule than extreme generalization of a rule. What I mean by this latter part is that drawing the rule outcomes (combination + progeny + mobility) can still be achieved without knowing what type of rule we are dealing with, purely by looking at the progeny and mobility, but it does move the decision making squarely out of the Rule module, where it ought to be in my opinion. We end up with:

type RuleType

= Simple

| Extended

| Generalized

type Error

= InvalidMobility String

| InvalidProgeny String

| UnknownCombination

| InvalidCombination

type alias Mobility = Set Int

type alias Combination a = Fragment a

type alias Progeny a = Fragment a

type alias Outcome a =

{ progeny : Progeny a

, mobility : Mobility

}

type Case a =

Case

{ outcome : Outcome a

, combination : Combination a

}

type Rule a

= Rule RuleType Span (List (Case a))The remainder of the Rule module provides constructor methods for all rule types, some modifiers for the progeny / mobility of rule cases and parameterized encoders and decoders (the user employing the Rule module must supply a union type to represent cell status and a encoder and decoder for that type). As an example, the encoder for a rule is given by:

encodeRule : (a -> Json.Encode.Value) -> Rule a -> Json.Encode.Value

encodeRule valueEncoder rule =

Json.Encode.object

[ ("rule-type", Json.Encode.string <| ruleTypeToString <| getType rule)

, ("span", Json.Encode.int <| getSpan rule)

, ("cases", Json.Encode.list (encodeCase valueEncoder) <| getCases rule)

]

encodeCase : (a -> Json.Encode.Value) -> Case a -> Json.Encode.Value

encodeCase valueEncoder (Case { outcome, combination }) =

Json.Encode.object

[ ("outcome", (encodeOutcome valueEncoder) outcome)

, ("combination", (encodeFragment valueEncoder) combination)

]

encodeOutcome : (a -> Json.Encode.Value) -> Outcome a -> Json.Encode.Value

encodeOutcome valueEncoder { progeny, mobility } =

Json.Encode.object

[ ("progeny", (encodeFragment valueEncoder) progeny)

, ("mobility", Json.Encode.set Json.Encode.int mobility)

]And in the fragment module:

toList : Fragment a -> List a

toList (Fragment left middle right) =

List.concat [List.reverse (Array.toList left), [middle], Array.toList right]

encodeFragment : (a -> Json.Encode.Value) -> Fragment a -> Json.Encode.Value

encodeFragment valueEncoder fragment =

Json.Encode.list valueEncoder (toList fragment)The user is this obliged to pass in a valueEncoder.

Unit testing

In our web app for mobile automata, we rely heavily on some specialized data structures (e.g. Fragment, Rule, …) and on JSON decoders and encoders. This incentivizes us to setup unit testing to catch bugs due to small inconsiderate modifications. Test files can be seen here.

With these test files in place we an omit configuration errors from the encoder and decoder logic as well as the Fragment and Rule modules, at least provided all significant cases are captured (the Fragment module for example was missing a test case that would have captured a hardcoded value messing up a high level experiment).

SVG interactivity

Creating a responsive and intuitive UI to modify a rule for any rule type was more difficult than imagined and in particular small local effects such as highlighting a combination cell when the mouse hovers over it can burden the Elm codebase with a need to keep track of this data in our model and propagating the data back all the way down to the drawing of the individual cell. For highlighting a cell as an illustration we have the following nested data in our model:

type alias Highlighted =

{ ruleCase : Case Cell

, index : Int

}

type Editing

= Progeny (Maybe Highlighted)

| Mobility (Maybe Highlighted)

type alias Settings =

{ speed : Int

, cellSize : Int

, editing : Editing

}

type alias Model =

{ settings : Settings

, rule : Rule Cell

, state : State

, canvas : Canvas

}To put it to use we define a couple of helper functions:

highlightProgeny : Case Cell -> Maybe Highlighted -> Int -> Bool

highlightProgeny ruleCase highlightedOption index =

case highlightedOption of

Just highlighted ->

if highlighted.ruleCase == ruleCase then

index == highlighted.index

else

False

Nothing -> False

highlightMobility : RuleType -> Case Cell -> Maybe Highlighted -> Int -> Bool

highlightMobility ruleType ruleCase highlightedOption index =

case highlightedOption of

Just highlighted ->

if highlighted.ruleCase == ruleCase then

case ruleType of

Simple ->

index == highlighted.index && not (Set.member index <| getMobility ruleCase) && index /= 0

Extended ->

index == highlighted.index && not (Set.member index <| getMobility ruleCase)

Generalized ->

index == highlighted.index

else

False

Nothing -> FalseWe use these functions in tandem with an annoying amount of bookkeeping code to propagate it all the way down to the proper view code.

In hindsight we could have used CSS properties to achieve this local effect (thanks to Elm Slack for the tip), omitting the need for propagating this model data all the way down to our view function responsible for drawing a cell and modifying the model when a change occurs. Given our interaction design this may be out of reach but it may be worth the time investment if it means we can slash a lot of code.

One other small change was the usage of the elm-community/typed-svg library for easier construction of SVG elements.

Scaling strategies

Another difference with the simple automata implementation is how we structure our model and messages. While we are not speaking of a terrible increase in model complexity, our mobile automata web app can benefit from a number of strategies mentioned by Feldman in this excellent talk.

One such strategy is to narrow the types in your functions; as you go down the function ladder (e.g. view -> viewControls -> viewSpecificControl -> …) it is best that the function signatures become increasingly concrete as opposed to passing the entire model down, having the function pick out the part it needs. This helps with debugging and narrowing down the purpose of each function.

Another strategy adopted consists of multiple levels of messages, one top level and several sublevels, depending on which parts of the model we want to modify. To best illustrate this, let’s revisit the model:

type alias Highlighted =

{ ruleCase : Case Cell

, index : Int

}

type Editing

= Progeny (Maybe Highlighted)

| Mobility (Maybe Highlighted)

type alias Settings =

{ speed : Int

, cellSize : Int

, editing : Editing

}

type alias Model =

{ settings : Settings

, rule : Rule Cell

, state : State

, canvas : Canvas

}Instead of designing a whole host of messages to deal with every variables in the Settings type, we can provide a top level message, and several mountable submessages:

type SettingsMsg

= ResizeCells Int

| UpdateEditing Editing

| IncreaseSpeed

| DecreaseSpeed

updateSettings : SettingsMsg -> Settings -> Settings

updateSettings settingsMsg settings =

case settingsMsg of

...

type Msg

= ...

| UpdateSettings SettingsMsg

| ...

update : Msg -> Model -> (Model, Cmd Msg)

update msg model =

case msg of

...

UpdateSettings settingsMsg ->

( { model

| settings = updateSettings settingsMsg model.settings

}

, Cmd.none

)

...In our view function, we construct a message by combining the top level and sublevel message. For example in the case of cell resizing we can use UpdateSettings << ResizeCells.

URL manipulation

Because we are no longer using a rule index we can’t paste a number into the URL as a query parameter to represent. When communicating with our custom element we pass a JSON string with the rule configuration. This functionality we can reuse for the URL.

For good reason we won’t be injecting JSON directly into the URL (even though the builder will take care of HTML quoting) and instead opt to encode and compress the data. In our rule update code we use the folkertdev/elm-flate, danfishgold/base64-bytes and elm/bytes libraries to achieve this:

UpdateRule ruleMsg ->

let

newRuleResult : Result Rule.Error (Rule Cell)

newRuleResult =

updateRule ruleMsg model.rule

in

case newRuleResult of

Err error ->

( model

, Cmd.none

)

Ok newRule ->

let

stringEncoder : String -> Bytes.Encode.Encoder

stringEncoder text =

Bytes.Encode.sequence

[ Bytes.Encode.unsignedInt32 BE (Bytes.Encode.getStringWidth text)

, Bytes.Encode.string text

]

encodedRule : String

encodedRule =

encodeRule encodeCell newRule

|> Json.Encode.encode 0

|> stringEncoder

|> Bytes.Encode.encode

|> Flate.deflateGZip

|> Base64.fromBytes

|> Maybe.withDefault ""

newUrl : String

newUrl =

Builder.relative []

[ Builder.string "rule" encodedRule

]

in

( { model

| rule = newRule

}

, Nav.pushUrl model.state.key newUrl

)And in reverse for decoding:

type alias Config =

{ rule : Result Error (Rule Cell)

}

parseConfig : Query.Parser Config

parseConfig =

Query.map Config (parseRule "rule")

parseRule : String -> Query.Parser (Result Error (Rule Cell))

parseRule representation =

Query.custom representation <| ( \stringList ->

case stringList of

[encodedConfiguration] ->

let

bytesDecoder : Bytes.Decode.Decoder String

bytesDecoder =

Bytes.Decode.unsignedInt32 BE

|> Bytes.Decode.andThen Bytes.Decode.string

jsonDecode : String -> Result Error (Rule Cell)

jsonDecode decodedJson =

case Json.Decode.decodeString (ruleDecoder symbolDecoder) decodedJson of

Ok rule ->

Ok rule

Err error ->

Err InvalidRule

in

encodedConfiguration

|> Base64.toBytes

|> Maybe.andThen Flate.inflateGZip

|> Maybe.andThen (Bytes.Decode.decode <| bytesDecoder)

|> Result.fromMaybe InvalidRule

|> Result.andThen jsonDecode

_ ->

Err InvalidRule

)Wrap up

The main roadblock in this iteration was not so much Elm itself, we had already tackled all relevant concept in the simple automata case. The main hurdle instead was in data modeling and to lesser extend scalability. The former is often very specific to the application one is building and will require a lot of experimentation on the developer’s part. For the latter we could rely on the worthwhile talks from established figures in the Elm community to guide us to better readability and maintenance of our code.

The resuls can be seen on our Vault.