BrainFartLab

Passion projects and ruminations related to IT development.

Project maintained by brainfartlab Hosted on GitHub Pages — Theme by mattgraham

Related

- QuizCraft: the reason

- QuizCraft: the frontend story

- QuizCraft: the backend story

- QuizCraft: the machine learning story

Quiz Craft: the machine learning story

Experience wise, machine learning falls somewhere in between frontend and backend for me. In university, many years ago, several courses were part of the mathematical engineering programme, back when data mining was still a hot topic. We saw least-support vector machines, decision trees and (simple) neural networks. Deep learning, using several layers of neural nodes, was but a whisper among students. Neural networks had a somewhat discredited status at the time, but research was picking up. I did not use any of my knowledge after I graduated.

Later on working at trivago, a hotel metasearch company, I was doing backend engineering in a team focusing on NLP, or natural language processing. I was more into the cloud computing, but I did pick up some concepts. Embeddings were ways to turn text into vectors. These vectors are then used to train the neural network, the specifics of which still elude me. My contact with the field was but a gentle caress. Watching AWS metrics just seemed more fun.

Which brings us to present day, where ChatGPT was introduced end of 2022, boasting a neural network with billions of neurons. Soon, everybody and their grandma’s where going to build next-gen whatevers. But hypes do settle, clearing the space for better implementations to come through. Github Copilot is helping engineers write code faster supposedly, AWS released CodeWhisperer as an alternative as have others. I’m sure other applications will make their entry at some point.

Our quiz application will allow us to get some hands on experience with ChatGPT, or any other LLM if desired. It’s not true machine learning, since we are mainly using a trained LLM and instructing it to do our bidding, also knows as prompt engineering. Perhaps in a later stage we can take a pre-existing model and fine tune it to our application context (quizzing), but that is not in scope right now. In the mean time open source can do the innovating thingy it always does and pave the way for the future. We have our OpenAI account, our billing is set up, now let’s create an API key and start building.

The journey

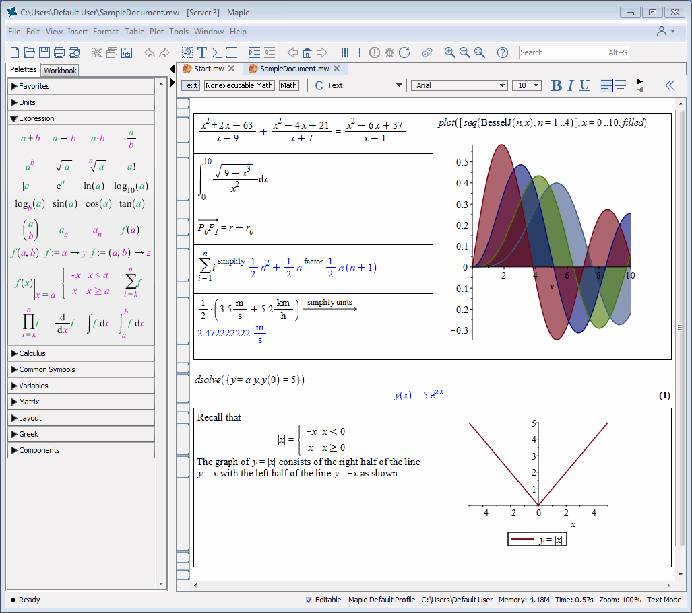

Time to dust off the Jupyter notebooks. Back when I was in university we used a tool called Maple to solve mathematical problems in a worksheet. This style allows for some very quick improvisation and prototyping, and years later Jupyter notebooks paved the way to use Python, R and Julia in a similar fashion.

Maplesoft’s Maple notebook style

Maplesoft’s Maple notebook style

A worksheet is comprised of cells with bits of code in it that one can execute. You can add, remove cells as you please and execute them in whatever order you like. It is no different than using a Python interpreter with an intuitive UI on top. It also becomes a mess very quickly if you are not careful. When you are in a creative bout it is not unlikely you end up with an incomprehensible bloated worksheet that becomes hard to manage. I recommend pruning and rearranging cells on a regular interval.

We got a tip from an enthusiast friend to look into langchain, a Python library that makes it easy to chain together steps interacting with LLMs hosted on OpenAI, HuggingFace and other portals. It was created by Harrison Chase, who partnered up with Andrew Ng to give a decent introduction course.

Going over the docs can feel a little overwhelming as you onboard the various concepts and try to make sense of it all. Try out the guides and as with the frontend story, try something from scratch to grasp the concepts.

I dove into the quiz setting fairly quickly and naively, starting with the simplest strategy of all: just ask the LLM to generate me some question related to some quiz keywords. See, I figured if the LLM was trained on a massive amount of data, or “corpus”, it could act as a database of sorts. So it probably already knows about whatever keywords I hurl at it. Well… yes and no. It definitely is knowledgeable, but it also has a tendency to hallucinate and come up with rather odd results. We want to attain some degree of consistency. One also needs to take into account that the LLM won’t have access to the latest news and its training data did not extend beyond September 2021, though that is changing.

Mapping to the langchain concepts, we use prompt engineering with a template instructing the LLM to play the part of an AI generating a question given some input keywords. Next up is to retrieve a format we can handily use in our Python code. For this we turn to output parsers, which are added as a section to our prompt template instructing the AI to return the quiz question as a JSON formatted string. We expand on the format and instruct the AI to include some wrong answers so we can ask multiple choice questions. Then we add another field to include a clarifying answer, which the user gets to see once they answered the question for some extra background.

Then we start including memory. We may want an undetermined amount of questions for the same keywords, so we include yet another section in our prompt, pasting in it all the previous generated material, instructing the AI to avoid repeating itself. We even create our own custom memory class using the conversation memory to filter out just the questions, so we can neatly include it as a list in the prompt.

So are we done? No, turns out the AI is a stubborn one, still asking the same questions but posed slightly differently. The wrong answers we ask the AI to include can also be hit or miss. Even when the wrong answers are not ridiculously and obviously wrong, they can be discerned from the correct answer due to their length, or their slightly different grammar. Sometimes the correct answer isn’t even correct. Turns out prompt engineering is harder than expected.

So we radically change things around. Let’s not depend on the AI anymore to act as a database. So we turn to document loading, using a Wikipedia wrapper to load documents for the quiz keywords. From these documents we derive facts, questions about facts to be precise. We instruct the AI to come up with one or more questions using our format instructions and some existing langchain classes, slightly modified for our use case. That seems to work, the questions are even distinct. This way we can also be more up to date with world events or newly acquired knowledge as Wikipedia gets updated.

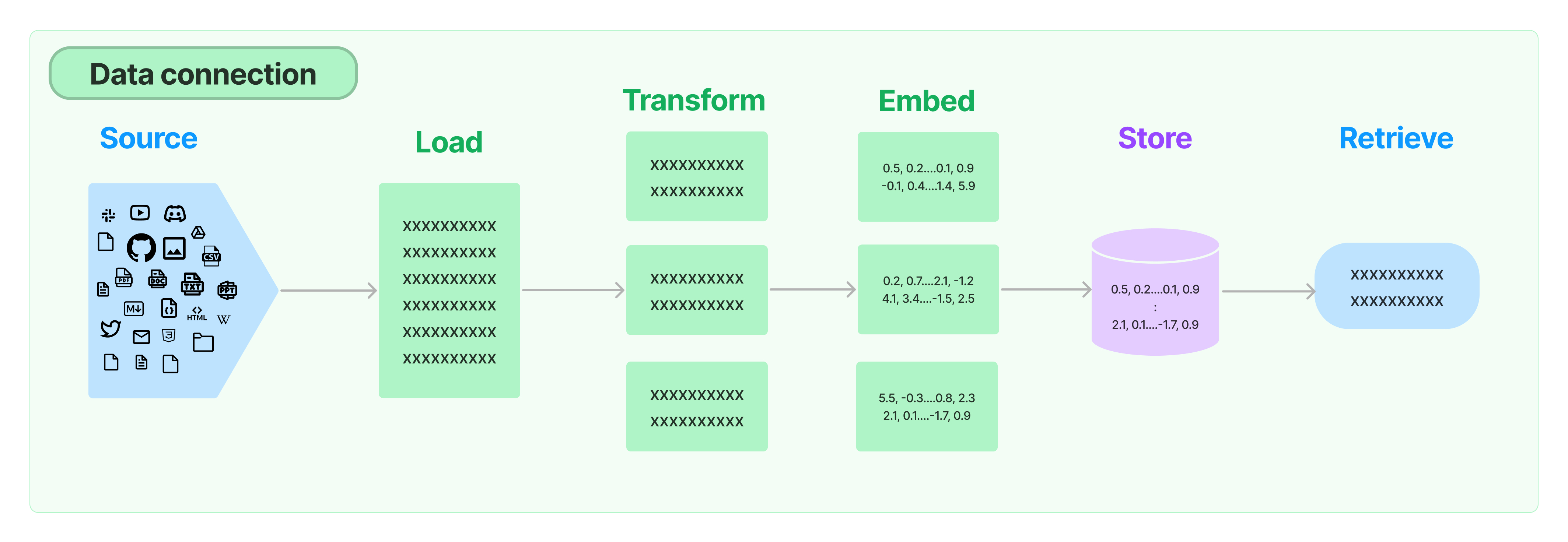

For some keywords we see that meaning becomes a thing. For example, for the keyword “elderflower” one of the documents is about some relatively unknown actor that played a role in some similarly unknown series called “Elderflower”. Fortunately, langchain allows us to create embeddings of the documents and put them in a vector store. On this we perform a similarity search using a retriever to omit documents that are less relevant. It works!

Document processing

Document processing

We abandon the implementation of generating one question at a time and feeding it back into the AI using memory altogether. We will assume we ask 15 questions always. We prompt the AI to just generate one or more questions per document. We start including some specifics as well: make the correct answer concise with no more than 5 words; make the wrong answers similar in style and format to the correct answer and so on. We pool the questions for each document, these form the initial list.

LLMs won’t solve all our problems, so we include some heuristic measures. After we obtain the initial batch of questions we do some preliminary filtering using string similarity algorithms to avoid the all too obvious questions. If the keywords happens to be “Netherlands”, the last thing we want is a question where the options are “Netherlands”, “France”, “Germany” and “England”. Gee, I wonder which one is the correct answer.

One of the shadier parts involved using the LLM to predict the answers to its own generated questions using the Wikipedia documents. The LLM then gets its own predictions alongside the original “correct answer”. If they do not match, chances are the correct answer ain’t so correct. I decide to just be practical about it. We can do theoreticals later.

Finally, we sample 15 questions from the remaining ones, or all if we fall below 15. The questions are stored in the backend and served to the player.

Deep dives

Document relevancy

We noted earlier we sometimes pull in completely unrelated documents from Wikipedia for our keywords. Whilst they definitely mention the keywords their relevance may be low. To counter this we perform a similarity search to the keywords using an LLM:

loader = WikipediaLoader(query=" ".join(keywords))

wiki_docs = loader.load()

data = wiki_docs

index = VectorstoreIndexCreator(

embedding=OpenAIEmbeddings(openai_api_key="..."),

vectorstore_cls=DocArrayInMemorySearch,

text_splitter=TokenTextSplitter(chunk_size=2500, chunk_overlap=0),

).from_documents(data)

retriever = index.vectorstore.as_retriever()

relevant_docs = retriever.get_relevant_documents(query=" ".join(keywords))Documents that happen to mention a keyword but have little to say about the actual keyword are dumped. If a document talks about an actor playing in a show called “Elderflower”, with little information on the show itself, we cannot use it. Discard.

Format instructions

Pretty standard, we use pydantic to describe the output:

class QuestionModel(BaseModel):

question: str = Field(

description="QUESTION: the question")

answer: str = Field(

description="ANSWER: the correct answer to the question")

wrong_answers: List[str] = Field(

description="WRONG ANSWERS: three incorrect answers")

clarification: str = Field(

description="CLARIFICATION: a clarifying answer")

class QuestionsModel(BaseModel):

questions: List[QuestionModel]

output_parser = PydanticOutputParser(pydantic_object=QuestionsModel)

template = """

Some instructions...

{format_instructions}

"""

prompt = PromptTemplate(

input_variables=["doc"],

template=template,

output_parser=output_parser,

partial_variables={

"format_instructions": output_parser.get_format_instructions(),

"keywords": "\n".join(game.keywords),

}

)

...

questions = []

for result in results:

doc_questions = output_parser.parse(result["text"])More importantly, we found that trying to provide extra instructions in the field descriptions of the model classes tend to be ignored entirely. Instead put them in the prompt for the LLM.

Heuristics

LLMs will not solve every little problem, and it can at times muck up even little simple tasks, so don’t be afraid to include some heuristics to correct where necessary. It also saves cost, sending less tokens to be processed by an LLM. In our case we eliminate trivial questions and answers with string similarity searches:

def contains_keyword(text: str, keywords: List[str]) -> bool:

def key(s):

return s.lower() # case insensitive

ng = NGram(text.split(), key=key)

for keyword in keywords:

test = ng.searchitem(keyword) # match every keyword with every word in the answer

if test and test[0][1] > 0.5:

return True

return False

def is_trivial(game: Game, question: Question) -> bool:

if contains_keyword(question.answer, game.keywords) and not any(contains_keyword(choice, game.keywords) for choice in question.wrong_answers):

return True # avoid situations where only the correct answer contains a keyword

return False

def review():

...

non_trivial_questions = []

for question in questions:

if not is_trivial(game, question):

non_trivial_questions.append(question)

...ChatGPT evaluating itself

Definitely the more questionable part of reviewing the generated questions. We filter out the question and “correct answer” that the LLM generated and have it use the documents to answer its own questions. The resulting prediction is then compared to the “correct answer” and graded. I have seen cases where it fails, comparing apples and oranges and deciding that somehow, they match. But then in other cases it does catch some pretty glaring mistakes.

temp = [

{

"query": question.question,

"answer": question.answer,

} for question in non_trivial_questions

] # extract question and "correct answer"

index = VectorstoreIndexCreator(

embedding=OpenAIEmbeddings(openai_api_key=self.openai_token),

text_splitter=TokenTextSplitter(chunk_size=2500, chunk_overlap=0),

vectorstore_cls=DocArrayInMemorySearch,

).from_documents(docs)

retriever = index.vectorstore.as_retriever()

llm = ChatOpenAI(openai_api_key=self.openai_token, temperature=0.0)

qa = RetrievalQA.from_chain_type(

llm=llm,

chain_type="stuff",

retriever=retriever, # LLM will answer using the documents

)

predictions = qa.apply(temp)

eval_chain = QAEvalChain.from_llm(llm)

graded_output = eval_chain.evaluate(temp, predictions) # LLM compares "correct answer" with predictions

final_questions = []

for i, grade in enumerate(graded_output):

if grade["text"] == "CORRECT":

final_questions.append(non_trivial_questions[i])Is it worth it? I am not sure, the runtime to create questions for a narrow keyword pulling in 4-5 Wikipedia documents is about 2 minutes, and the review part takes about half that time.

Wrap up

This is only a first iteration, and prompt engineering is most definitely an iterative process, with tweaks required depending on what sort of keywords are provided. We go over some issues that will need work.

Narrow or broad topic

Determine if the keywords constitute a narrow or a broad topic; broad topics sometimes lead to Wikipedia category pages with links to other pages, we don’t follow these through. Then again, including all this extra material drives up both time and price, so some sampling would be beneficial.

For narrow topics we may need to expand beyond Wikipedia and perform Google Searches. How do we filter out the relevant documents in such a setting? If we search for “soccer”, can we expect to hit gold with a history page of all World Cup facts, or will we chance upon a store selling soccer equipment? Does the player know how much a Copa Mundial shoe pair costs right now, seasonal discounts included? Perhaps couple the keywords with some additional ones, such as “history”, “fun facts”, “celebrities” and others when we perform Google searches.

Unique questions

Right now I simply pool all the questions from each document, but there will be circumstances where the same piece of information is included in multiple Wikipedia pages. We would need to include another post processing step to retain only the unique questions, provided the LLM is up to the job.

Subjective vs objective

The preference is for the LLM to generate only objective questions. This means it should use only matter of factly bits of information from the document. But can the LLM discern between subjective and objective to a great enough extent? What do we consider objective? Definitions, quantitative statements would definitely fall under this umbrella. We are also at the mercy of the objectivity of Wikipedia contributors.

Context

Currently, an LLM may come up with questions working from the assumption that the user has read the document and is going to take a test. So once in a while the question is of the form “What does the document say about …?”. But the documents are obfuscated from the player, better prompting will need to eliminate these assumptions. Such mistakes also expose internals of the application, which is better avoided.

Relevancy

We discussed filtering out irrelevant documents before, but perhaps we should take the Wikipedia approach with their “disambiguation” pages. If a player provides “Steve Carl” as a keyword, they’re likely referring to a wrester, not to the show “Family Matters” with two characters named Steve (Urkel) and Carl.

Less wrong wrong answers

Take a quiz question asking you which year Belgium became independent, with the four options: 1825, 1830, 1832, 1835. Notice something? A trained eye will see that three of the years are differing in increments of 5. However, I will need to give credit to the LLM, the correct answer is 1830. Sneaky bastard.